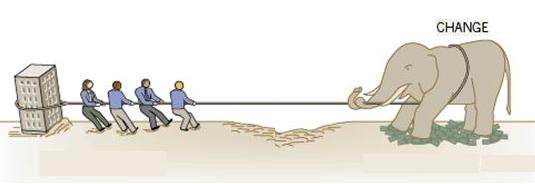

The goal of planned organizational change is to find new or improved ways of using resources and capabilities in order to increase an organization’s ability to create value and improve returns to its stakeholders. An organization in decline may need to restructure its resources to improve its fit with the environment. At the same time even a thriving organization may need to change the way it uses its resources so that it can develop new products or find new markets for its existing products. In the last decade, over half of all Fortune 500 companies have undergone major organizational changes to allow them to increase their ability to create value. One of the most well-documented findings from studies have revealed that organizations and their members often resist change. In a sense, this is positive. It provides a degree of stability and predictability to behavior. If there weren’t some resistance, organizational behavior would take on characteristics of chaotic randomness.

Resistance to change can also be a source of functional conflict. For example, resistance to a reorganization plan or a change in a product line can stimulate a healthy debate over the merits of the idea and result in a better decision. But there is a definite downside to resistance to change. It hinders adaptation and progress. Resistance to change doesn’t necessarily surface in standardized ways. Resistance can be overt, implicit, immediate or deferred. It is easiest for management to deal with resistance when it is overt and immediate : For instance a change is proposed and employees quickly respond by voicing complaints, engaging in a work slowdown, threatening to go on strike, or the like. The greater challenge is managing resistance that is implicit or deferred. Implicit resistance efforts are more subtle — loss of loyalty to the organization, loss of motivation to work, increased errors or mistakes, increased absenteeism due to sickness and hence, more difficult to recognize. Similarly, deferred actions cloud the link between the source of the resistance and the reaction to it. A change may produce what appears to be only a minimal reaction at the time it is initiated, but then resistance surfaces weeks, months or even year later. Or a single change that in and of itself might have little impact becomes the straw that breaks the company’s back. Reactions to change can build up and then explode in some response that seems to tally out of proportion to the change action it follows. The resistance, of course, has merely been deferred and stockpiled what surfaces is a response to an accumulation of previous changes.

Sources of Resistance to Change in Organizations

Sources of resistance could be at the individual level or at the organizational level. Some times these sources can overlap.

Individual Factors

Individual sources of resistance to change reside in basic human characteristics such as perceptions, personalities and needs. There are basically four reasons why individuals resist change.

- Habit : Human beings are creatures of habit. Life is complex enough; we do not need to consider the full range of options for the hundreds of decisions we have to make every day. To cope with this complexity, we all rely on habits of programmed responses. But when confronted with change, this tendency to respond in our accustomed ways become a source of resistance. So when your office is moved to a new location, it means you’re likely to have to change many habits, taking a new set of streets to work, finding a new parking place, adjusting to a new office layout, developing a new lunch time routine and so on. Habit are hard to break. People have a built in tendency to their original behavior, a tendency to stymies change.

- Security : People with a high need for security are likely to resist change because it threatens their feeling of safety. They feel uncertain and insecure about what its outcome will be. Worker might be given new tasks. Role relationships may be reorganized. Some workers might lose their jobs. Some people might benefit at the expense of others. Worker’s resistance to the uncertainty and insecurity surrounding change can cause organizational inertia. Absenteeism and turnover may increase as change takes place and workers may become uncooperative, attempt to delay or slow the change process and otherwise passively resist the change in an attempt to quash it.

- Selective Information Processing : Individuals shape their world through their perceptions. They selectively process information in order to keep their perceptions intact. They hear what they want to hear. They ignore information that challenges the world they have created. Therefore, there is a general tendency for people to selectively perceive information that is consistent with their existing views of their organizations. Thus, when change takes place workers tend to focus only on how it will affect them on their function or division personally. If they perceive few benefits they may reject the purpose behind the change. Not surprisingly it can be difficult for an organization to develop a common platform to promote change across the organization and get people to see the need for change in the same way.

- Economic Factors : Another source of individual resistance is concern that change will lower one’s income. Changes in job tasks or established work routines also can arouse economic fears if people are concerned they won’t be able to perform the new tasks or routines to their previous standards, especially when pay is closely tied to productivity. For example, the introduction of Total Quality Management (TQM) means production workers will have to learn statistical process control techniques, some may fear they’ll be unable to do so. They may, therefore, develop a negative attitude towards TQM or behave dysfunctionally if required to use statistical techniques.

Group Level Factors

Much of an organization’s work is performed by groups and several group characteristics can produce resistance to change :

- Group Inertia : Many groups develop strong informal norms that specify appropriate and inappropriate behaviors and govern the interactions between group members. Often change alters tasks and role relationships in a group; when it does, it disrupts group norms and the informal expectations that group members have of one another. As a result, members of a group may resist change because a whole new set of norms may have to be developed to meet the needs of the new situation. Group think is a pattern of faulty decision making that occurs in cohesive groups when members discount negative information in order to arrive at a unanimous agreement. Escalation of commitment worsens this situation because even when group members realize that their decision is wrong, they continue to pursue it because they are committed to it. These group processes make changing a group’s behavior very difficult. And the more important the group’s activities are to the organization, the greater the impact of these processes are on organizational performance.

- Structural Inertia : Group cohesiveness, the attractiveness of a group to its members, also affects group performance. Although, some level of cohesiveness promotes group performance, too much cohesiveness may actually reduce performance because it stifles opportunities for the group to change and adapt. A highly cohesive group may resist attempts by management to change what it does or even who is a member of the group. Group members may unite to preserve the status quo and to protect their interests at the expense of other groups. Organizations have built-in mechanism to produce stability. For example, the selection process systematically selects certain people in and certain people out. Training and other socialization techniques reinforce specific role requirements and skills. Formalization provides job descriptions, rules and procedures for employees to follow. The people who are hired into an organization are chosen for fit; they are then shaped and directed to behave in certain ways. When an organization is confronted with change, this structural inertia acts as a counter balance to sustain stability.

- Power Maintenance : Change in decision-making authority and control to resource allocation threatens the balance of power in organizations. Units benefiting from the change will endorse it, but those losing power will resist it, which can often slow or prevent the change process. Managers, for example, often resist the establishment of self-managed work teams. Or, manufacturing departments often resist letting purchasing department control input quality. There are even occasions when a CEO will resist change, denying that it is his responsibility to promote socially responsible behavior through out a global network.

- Functional Sub-optimization : Differences in functional orientation, goals and resources dependencies can cause changes that are seen as beneficial to one functional unit to be perceived as threatening to other. Functional units usually think of themselves first when evaluating potential changes. They support those that enhance their own welfare, but resist the ones that reduce it or even seem inequitable.

- Organizational Culture : Organizational culture, that is, established values, norms and expectations, act to promote predictable ways of thinking and behaving. Organisational members will resist changes that force them to abandon established assumptions and approved ways of doing things.

Managers sometimes mistakenly assume that subordinates will perceive the desired changes as they do; thus, they have difficulty in understanding the resistance. A key task is to determine and understand the reasons behind people’s resistance when it occurs. Then the challenge is to find ways to reduce it or overcome that resistance.