Market Activated Corporate Strategy (MACS) Framework was developed in the late 1980s. But it wasn’t developed at once. There were several predecessors to this framework.

Once of the first can be the BCG Growth-Share Matrix. This matrix represents the market growth rate and the relative market share, and according to the level, the business units were divided into 4 categories. It was used very often before, but over the time more comprehensive tools were designed, to eliminate the weaknesses of BCG Matrix, like the fact that is takes into consideration only two factors, avoiding many many others that have a huge impact on profitability. BCG Matrix also assumes the independence of each business unit, therefore it leads to underestimation of the interconnection that often exists (as “Dogs”, for example, sometimes help in gaining competitive advantage)

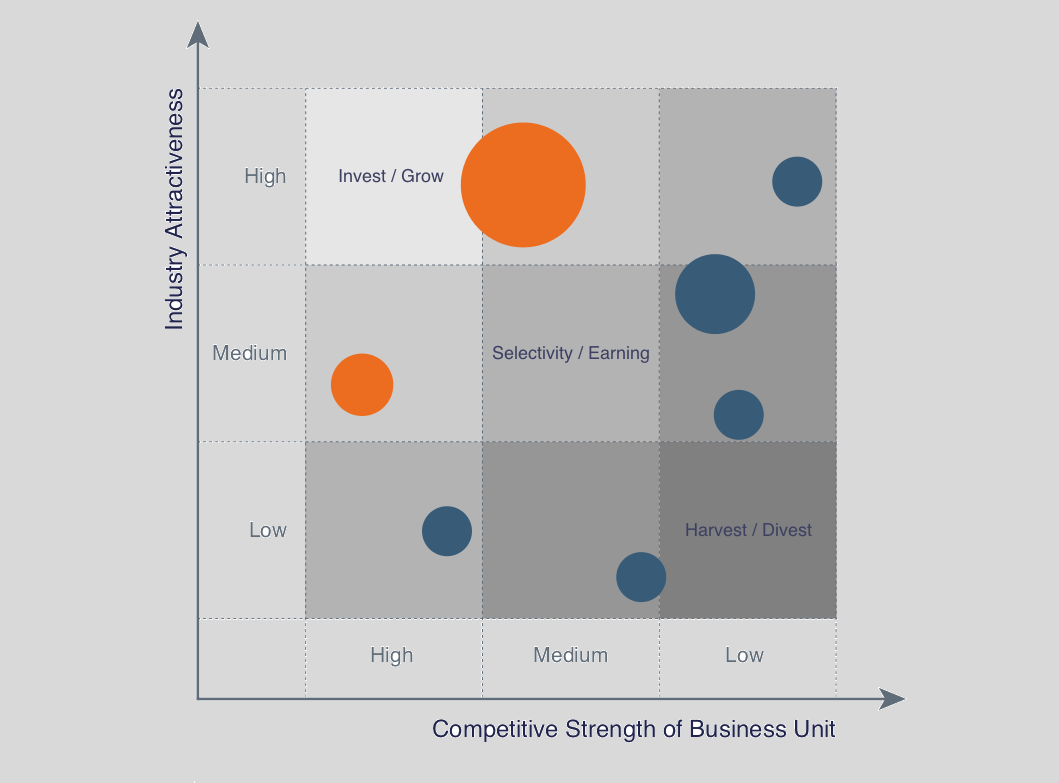

Another predecessor is the old nine-box matrix, developed by McKinsey. It covers industry attractiveness and competitive strength of the business unit, and has three levels: high, medium and low. McKinsey’s nine-box strategy matrix, was very popular in the 1970s, taking into a consideration the attractiveness of a given industry along one axis and the competitive position of a particular business unit in that industry along the other. Thus, the matrix could reduce the value-creation potential of a company’s many business units to a single, digestible chart.

However, the nine-box matrix applied only to product markets: those in which companies sell goods and services to customers. Because a comprehensive strategy must also help a parent company win in the market for corporate control — where business units themselves are bought, sold, spun off, and taken private — a analytical tool called the market activated corporate strategy (MACS) framework was developed.

Market Activated Corporate Strategy (MACS) Framework

MACS (Market Activated Corporate Strategy) framework represents much of McKinsey’s most recent thinking in strategy and finance, it is a framework that offers a systematic approach for the multi-business corporation to prioritize its investments among its business units.

How should a corporation decide whether to buy, sell, or keep a business unit? In the late 1980s, McKinsey developed its market activated corporate strategy (MACS) framework, which answered that question in a surprising way. The obvious considerations – the attractiveness of the industry in which the unit competes and its competitiveness within that industry – are both relevant, but the acid test is which company can extract the greatest value from the business. If the present owner should be that company, it probably ought to keep even a mediocre or poorly performing unit. A company should make sure that it is the best possible owner of each of its business units – not simply hold on to units that are strong in themselves.

The key insight of MACS is that a corporation’s ability to extract value from a business unit relative to other potential owners should determine whether the corporation ought to hold onto the unit in question.

In the MACS matrix, the axes from the old nine-box framework measuring the industry’s attractiveness and the business unit’s ability to compete have been collapsed into a single horizontal axis, representing a business unit’s potential for creating value as a stand-alone enterprise. The vertical axis in MACS represents a parent company’s ability, relative to other potential owners, to extract value from a business unit. And it is this second measure that makes MACS unique.

Managers can use MACS just as they used the nine-box tool, by representing each business unit as a bubble whose radius is proportional to the sales, the funds employed, or the value added by that unit. The resulting chart can be used to plan acquisitions or divestitures and to identify the sorts of institutional skill-building efforts that the parent corporation should be engaged in.

- The horizontal dimension: Business unit’s potential of creating value as a stand-alone enterprise. The horizontal dimension of a MACS matrix shows a business unit’s potential value as an optimally managed stand-alone enterprise. This measures the optimal value of a business, sometimes it can be qualitative. When more precise information is needed, the manager can use the net present value of the business unit and then compare it with other units (factors like sales, value added, or funds employed can be also included).

- The vertical dimension: Parent Company’s ability to extract value from the business unit. The vertical axis of the MACS matrix measures a corporation’s relative ability to extract value from each business unit in its portfolio. If the parent company can extract the most value from the business unit than could be done by anyone else, this company is the owner that can really create the most value from the assets and these business units should be kept.

There are several qualification for the company that can highlight its ability to the the owner of the business:

- The parent corporation may be able to envision the future shape of the industry-and therefore to buy, sell, and manipulate assets in a way that anticipates a new equilibrium.

- It may excel at internal control: cutting costs, squeezing suppliers.

- It may have other businesses that can share resources with the new unit or transfer intermediate products or services to and from it.

There may be financial or technical factors that determine, to one extent or other, the natural owner of a business unit. These can include taxation, owners’ incentives, imperfect information, and differing valuation techniques.

Of course, the MACS matrix is just a snapshot. The manager’s objective is to find the combination of corporate capabilities and business units that provides the best overall scope for creating value with the usage of all available tools for analysis, including the MACS.

If the parent company is best suited to extract value from a unit, it often makes no sense to sell, even if that unit doesn’t compete in a particularly profitable industry. Conversely, if a parent company determines that it is not the best possible owner of a business unit, the parent maximizes value by selling it to the most appropriate owner, even if the unit happens to be in a business that is fundamentally attractive. In short, the “market activated corporate strategy framework” prompts managers to view their portfolios with an investor’s value-maximizing eye.

But even taking into consideration these factors, MACS is still useful and helps in company’s assessment and planning process. In combination with other tools, MACS represent a reliable combination of data, required by company’s management.