Apple was founded by Steve Jobs and Stephen Wozniak in 1976; Apple Computers revolutionized the personal computer industry. Apple Computers Inc is considered to be one of the innovators in the computer industry. It brought about different changes to the industry; these changes are still visible in the present. The company’s products were used as a basis by other computer company’s in designing the specifications and physical characteristics of their product. It also serves as a meter of how products are designed. The company offers various products for the different market it targets. The products made by the company offer something different.

We can describe Apple’s business strategy in terms of product differentiation and strategic alliances.

Product Differentiation

Product Differentiation

Apple prides itself on its innovation. When reviewing the history of Apple, it is evident that this attitude permeated the company during its peaks of success. For instance, Apple pioneered the PDA market by introducing the Newton in 1993. Later, Apple introduced the easy-to-use iMac in 1998, and updates following 1998. It released a highly stable operating system in 1999, and updates following 1999. Apple had one of its critical points in history in 1999 when it introduced the iBook. This completed their “product matrix”, a simplified product mix strategy formulated by Jobs. This move allowed Apple to have a desktop and a portable computer in both the professional and the consumer segments. The matrix is as follows:

| Professional Segment | Consumer Segment | |

| Desktop | G3 | iMac |

| Portable | PowerBook | iBook |

In 2001, Apple hit another important historical point by launching iTunes. This marked the beginning of Apple’s new strategy of making the Mac the hub for the “digital lifestyle”. Apple then opened its own stores, in spite of protests by independent Apple retailers voicing cannibalization concerns. Then Apple introduced the iPod, central to the “digital lifestyle” strategy. Philip W. Schiller, VP of Worldwide Product Marketing for Apple, stated, “iPod is going to change the way people listen to music.” He was right.

Apple continued their innovative streak with advancements in flat-panel LCDs for desktops in 2002 and improved notebooks in 2003. In 2003, Apple released the iLife package, containing improved versions of iDVD, iMovie, iPhoto, and iTunes. In reference to Apple’s recent advancements, Jobs said, “We are going to do for digital creation what Microsoft did for the office suite productivity.” That is indeed a bold statement. Time will tell whether that happens.

Apple continued its digital lifestyle strategy by launching iTunes Music Store online in 2003, obtaining cooperation from “The Big 5” Music companies–BMG, EMI, Sony Entertainment, Universal, Warner. This allowed iTunes Music Store online to offer over 200,000 songs at introduction. In 2003, Apple released the world’s fastest PC (Mac G5), which had dual 2.0GHz PowerPC G5 processors.

Product differentiation is a viable strategy, especially if the company exploits the conceptual distinctions for product differentiation. Those that are relevant to Apple are product features, product mix, links with other firms, and reputation. Apple established a reputation as an innovator by offering an array of easy-to-use products that cover a broad range of segments. However, its links with other firms have been limited, as we will discuss in the next section on strategic alliances.

There is economic value in product differentiation, especially in the case of monopolistic competition. The primary economic value of product differentiation comes from reducing environmental threats. The cost of product differentiation acts as a barrier to entry, thus reducing the threat of new entrants. Not only does a company have to bear the cost of standard business, it also must bear the costs associated with overcoming the differentiation inherent in the incumbent. Since companies pursue niche markets, there is a reduced threat of rivalry among industry competitors.

A company’s differentiated product will appear more attractive relative to substitutes, thus reducing the threat of substitutes. If suppliers increase their prices, a company with a differentiated product can pass that cost to its customers, thus reducing the threat of suppliers. Since a company with a differentiated product competes as a quasi-monopoly in its market segment, there is a reduced threat of buyers. With all of Porter’s Five Forces lower, a company may see economic value from a product differentiation strategy.

A company attempts to make its strategy a sustained competitive advantage. For this to occur, a product differentiation strategy that is economically valuable must also be rare, difficult to imitate, and the company must have the organization to exploit this. If there are fewer firms differentiating than the number required for perfect competition dynamics, the strategy is rare. If there is no direct, easy duplication and there are no easy substitutes, the strategy is difficult to imitate.

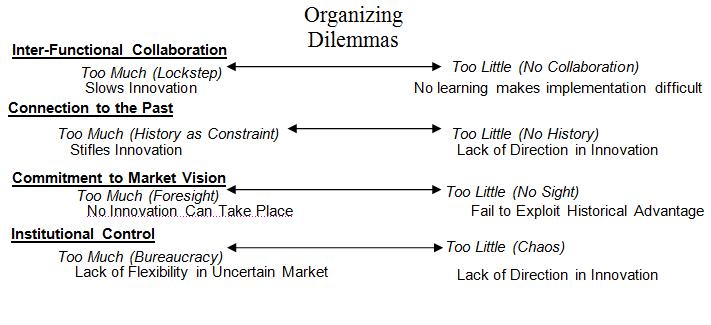

There are four primary organizing dilemmas when considering product differentiation as a strategy. They are as depicted below.

To resolve these dilemmas, there must be an appropriate organization structure. A U-Form organization resolves the inter-functional collaboration dilemma if there are product development and product management teams. Combining the old with the new resolves the connection to the past dilemma. Having a policy of experimentation and a tolerance for failure resolves the commitment to market vision dilemma. Managerial freedom within broad decision-making guidelines will resolve the institutional control dilemma.

To resolve these dilemmas, there must be an appropriate organization structure. A U-Form organization resolves the inter-functional collaboration dilemma if there are product development and product management teams. Combining the old with the new resolves the connection to the past dilemma. Having a policy of experimentation and a tolerance for failure resolves the commitment to market vision dilemma. Managerial freedom within broad decision-making guidelines will resolve the institutional control dilemma.

Five leadership roles will facilitate the innovation process: Institutional Leader, Critic, Entrepreneur, Sponsor, and Mentor. The institutional leader creates the organizational infrastructure necessary for innovation. This role also resolves disputes, particularly among the other leaders. The critic challenges investments, goals, and progress. The entrepreneur manages the innovative unit(s). The sponsor procures, advocates, and champions. The mentor coaches, counsels, and advises.

Apple had issues within its organization. In 1997, when Apple was seeking a CEO acceptable to Steve Jobs, Jean-Louis Gassee (then-CEO of Be, ex-Products President at Apple) commented, “Right now the job is so difficult, it would require a bisexual, blond Japanese who is 25 years old and has 15 years’ experience!” Charles Haggerty, then-CEO of Western Digital, said, “Apple is a company that still has opportunity written all over it. But you’d need to recruit God to get it done.” Michael Murphy, then-editor of California Technology Stock Letter, stated, “Apple desperately needs a great day-to-day manager, visionary, leader and politician. The only person who’s qualified to run this company was crucified 2,000 years ago.”

Since Jobs took over as CEO in 1997, Apple seems to have resolved the innovation dilemmas, evidenced by their numerous innovations. To continue a product differentiation strategy, Apple must continue its appropriate management of innovation dilemmas and maintain the five leadership roles that facilitate the innovation process.

Strategic Alliances

Apple has a history of shunning strategic alliances. On June 25, 1985, Bill Gates sent a memo to John Sculley (then-CEO of Apple) and Jean-Louis Gassee (then-Products President). Gates recommended that Apple license Macintosh technology to 3-5 significant manufacturers, listing companies and contacts such as AT&T, DEC, Texas Instruments, Hewlett-Packard, Xerox, and Motorola. (Linzmayer, 245-8) After not receiving a response, Gates wrote another memo on July 29, naming three other companies and stating, “I want to help in any way I can with the licensing. Please give me a call.” In 1987, Sculley refused to sign licensing contracts with Apollo Computer. He felt that up-and-coming rival Sun Microsystems would overtake Apollo Computer, which did happen.

Then, Sculley and Michael Spindler (COO) partnered Apple with IBM and Motorola on the PowerPC chip. Sculley and Spindler were hoping IBM would buy Apple and put them in charge of the PC business. That never came to fruition, because Apple (with Spindler as the CEO) seemed contradictory and was extraordinarily difficult in business dealings. Apple turned the corner in 1993. Spindler begrudgingly licensed the Mac to Power Computing in 1993 and to Radius (who made Mac monitors) in 1995. However, Spindler nixed Gateway in 1995 due to cannibalization fears. Gil Amelio, an avid supporter of licensing, took over as CEO in 1996. Under Amelio, Apple licensed to Motorola and IBM. In 1996, Apple announced the $427 million purchase of NeXT Software, marking the return of Steve Jobs. Amelio suddenly resigned in 1997, and the stage was set for Jobs to resume power.

Jobs despised licensing, calling cloners “leeches”. He pulled the plug, essentially killing its largest licensee (Power Computing). Apple subsequently acquired Power Computing’s customer database, Mac OS license, and key employees for $100 million of Apple stock and $10 million to cover debt and closing costs. The business was worth $400 million.

A massive reversal occurred in 1997 and 1998. In 1997, Jobs overhauled the board of directors and then entered Apple into patent cross-licensing and technology agreements with Microsoft. In 1998, Jobs stated that Apple’s strategy is to “focus all of our software development resources on extending the Macintosh operating system. To realize our ambitious plans we must focus all of our efforts in one direction.” This statement was in the wake of Apple divesting significant software holdings (Claris/FileMaker and Newton).

There is economic value in strategic alliances. In the case of Apple, there was the opportunity to manage risk and share costs facilitate tacit collusion , and manage uncertainty. It would have been applicable to the industries in which Apple operated. Tacit collusion is a valid source of economic value in network industries, which the computer industry is. Managing uncertainty, managing risk, and sharing costs are sources of economic value in any industry. Although Apple eventually realized the economic value of strategic alliances, it should have occurred earlier.

The following are some comments about Apple’s no-licensing policy.

“If Apple had licensed the Mac OS when it first came out, Window wouldn’t exist today.” – Jon van Bronkhorst, “The computer was never the problem. The company’s strategy was. Apple saw itself as a hardware company; in order to protect our hardware profits, we didn’t license our operating system. We had the most beautiful operating system, but to get it you had to buy our hardware at twice the price. That was a mistake. What we should have done was calculate an appropriate price to license the operating system. We were also naïve to think that the best technology would prevail. It often doesn’t.” – Steve Wozniak, Apple cofounder

“If we had licensed earlier, we would be the Microsoft of today.” – Ian W. Diery, Apple Executive VP, I am aware that I am known as the Great Satan on licensing…I was never for or against licensing. I just did not see how it would make sense. But my approach was stupid. We were just fat cats living off a business that had no competition.” – Jean-Louis Gassee, Be CEO and ex-CEO of Apple, admitting he made a strategic mistake.

A strategic alliance can be a sustained competitive advantage if it is rare, difficult to imitate, and the company has an organization to exploit it. If the number of competing firms implementing a similar strategic alliance is relatively few, the strategy is rare. If there are socially complex relations among partners and there is no direct duplication, the strategy is difficult to imitate. When organizing for strategic alliances, a firm must consider whether the alliance is non-equity or equity. A non-equity alliance should have explicit contracts and legal sanctions. An equity alliance should have contracts describing the equity investment. There are some substitutes for an equity alliance, such as internal development and acquisitions. However, the difficulties with these drive the formation of strategic alliances. It is vital to remember, “Commitment, coordination, and trust are all important determinants of alliance success.”